Looking for Representation

Looking for Representation

By Aliya Gibbons

Along with the change of the school mascot, the Board of Education also sanctioned audits of our schools’ curriculum with the focus on promoting more diverse content in history and English courses. Some changes can already be seen, like the addition of the book Just Mercy written by Bryan Stevenson to the freshman English classes (makes me wish I was a freshman right now!). While talking about diversifying the curriculum with respect to race and gender, we seem to have left out LGBTQ+ representation from the discussion. As a student of GHS, I cannot speak to every conversation that the Board, the administration, or the departments have had, but I can comment on what I have seen as a member of the LGBTQ+ community.

The issue with the history curriculum is a little complicated. It was one of those things that always bothered me and I could not pinpoint exactly what was wrong with it. It wasn’t until a couple weeks ago, as I was trying to articulate it to someone, that I finally was able to pull it apart. The importance of representation in education is fairly obvious: students being able to see themselves reflected in their learning helps to develop a sense of identity, confidence, and self-worth. I have written quite a few English essays on this very topic, and every time I am struck by the importance of seeing yourself in your curriculum. This way of looking at the problem paints representation as an added bonus, not something that is integral to a student’s understanding of themselves.

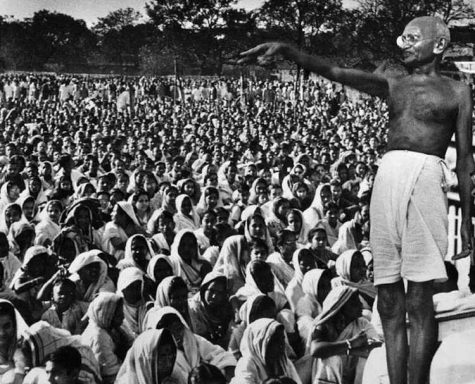

In history classes, we learn about social movements, the abolitionists, women’s suffrage, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Women’s Movement of the 70s-80s. I learned about most of these at least once, if not twice, from seventh grade until now. But every time, without fail, we always skip over the gay rights movement in the 80s that continued into the early 2000s. Not only does this exclude an important part of our country’s history, but it isolates students who identify as a part of the LGBTQ+ community. The message this sends to students is this: we, as a community, have decided that racism and sexism are bad and uncontroversially so (whether or not we act on that is a whole other thing), but gay rights? we need to think about that one a little longer. We teach what is accepted truths through the eyes of the community, things that are uncontroversial and are norms. So, this exclusion of the gay rights movement from our curriculum sends a message that our community has not decided if gay rights is an accepted truth. We still need to think about whether or not homophobia is truly bad, if being queer is okay, or if gay and trans rights are accepted. In the meantime, queer students are left to feel unseen. That they shouldn’t talk about their identity for fear of repercussions. That a part of who they are is not yet a ‘norm’. Essentially, we are telling queer students that they themselves are controversial.

Some members of the community will say that adding more ‘diverse’ content to our English curriculum will wash out and erase the traditional history that is so often taught in classrooms. I truly do understand that concern. I am not trying to argue that we should no longer teach the Civil Rights Movement, World War II, or Vietnam. These pieces of history teach us about our history and the role of the United States in world events. However, at its core, history classes are supposed to teach us the legacy of our country, the errors that we have made, and the cultures that have formed. Whether we recognize it or not, the queer community is a part of the American culture and has a huge historical past in the United States. From Stonewall, to Bayard Rustin, to Elenor Roosevelt. Not just this history of the LGBTQ+ movement and rights, but the importance of historical gay figures. All in all, including the queer perspective in history classes, makes them more accurate, makes the students more knowledgable (which is the goal of any class), and demonstrates to LGBTQ+ students that they are accepted.

A 2019 study conducted by the organization GLSEN, founded by a group of teachers in 1990 to promote LGTBQ+ representation in classrooms, found that LGBTQ+ students in schools with LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum “felt [a] greater belonging to their school community”. Not only this, but schools’ queer students with a representative curriculum were 19.7% less likely to hear homophobic slurs from their peers and 11.8% less likely to miss school because they felt unsafe due to their sexual orientation or gender expression compared to queer students without a representative curriculum. This brings up an important point to make: not only does an inclusive curriculum benefit queer students with respect to promoting positive self-images, but it also helps students outside of the LGBTQ+ community to challenge their preconceived stereotypes and misconceptions. Including LGBTQ+ history into the curriculum creates an overall more accepting and safe environment for students to learn in.

The school system has taken steps towards this direction. An ‘empathy’ interview conducted by Dr. Donald Siler of the University of St. Joseph in order to understand how students feel represented in the school system, is one good example. But, it is important to recognize that steps to move in this direction will be controversial, they will be met with resistance from the community just like the other curriculum changes have. But the problem with waiting for the entire community to support a change like this is that it could take a long time, if it ever happens at all, and meanwhile, queer students are left to feel like they are not a respected and valued part of this community. I know that the well-being of our students and adolescent community members is the first priority of the administration, the Board of Education, and the Guilford community. The opinions of adults in the community should not prevent progress that will help make school a safer place that focuses on the wellbeing of all students.